Behind the Book

THE REBIRTH OF INDIAN ART

The beginnings of India’s modern art movement are central to the narrative of Inside the Mirror, set in 1950s Bombay, now known by its Marathi name Mumbai. Jaya Malhotra, a medical student and ambitious young painter, who is my novel’s central figure, is drawn to modernism for the bold statement it provokes the artist to make about herself and her world. Through Jaya’s pursuit of art, the novel looks at how Indian painting reemerged as a radically new medium in the aftermath of colonialism, led by a contingent of rebel artists borrowing from the visual language of Picasso and the School of Paris painters.

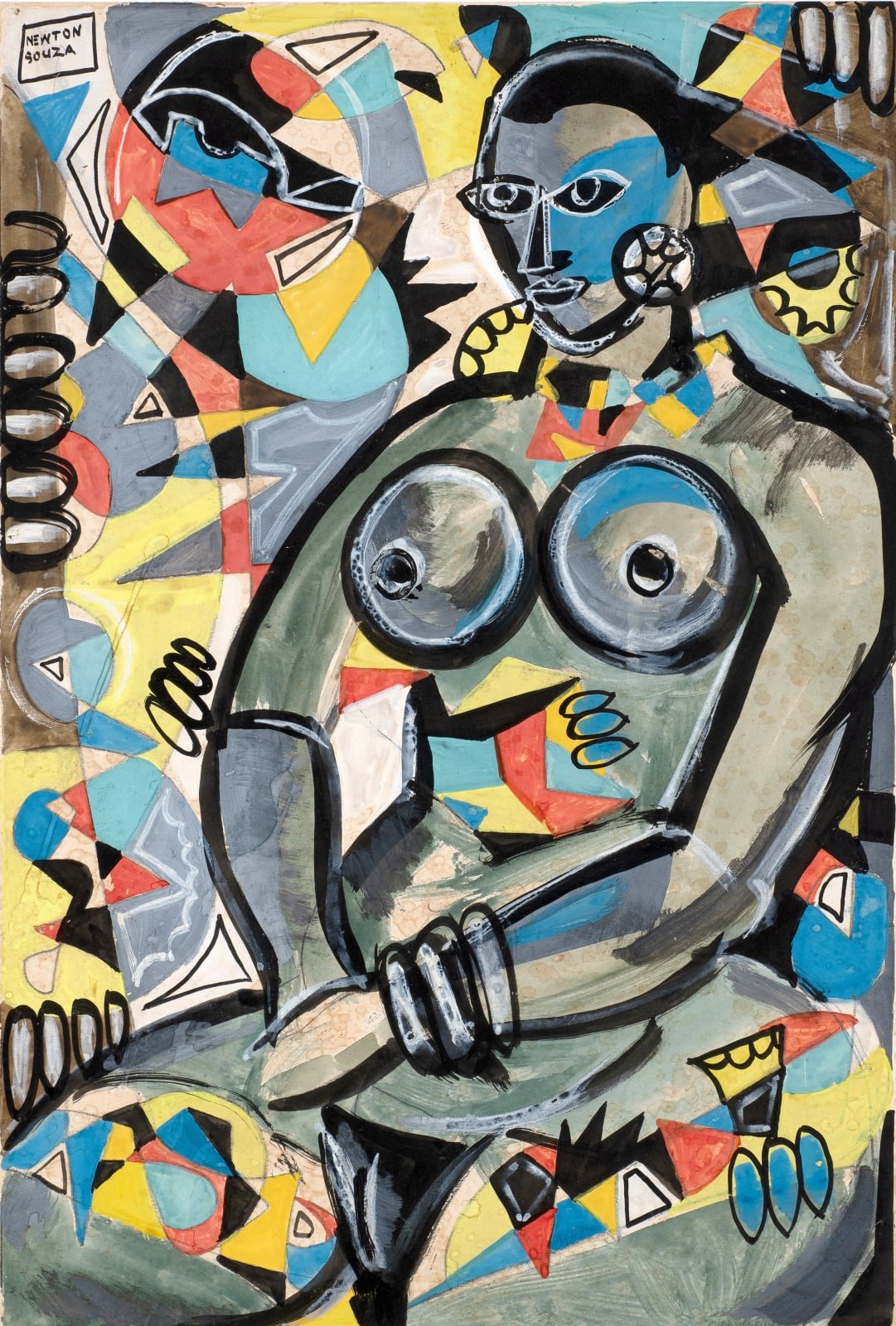

Francis Newton Souza, Untitled (Nude), 1950

The rise of Indian modernism followed two centuries of British domination over the Subcontinent that not only disrupted political and economic systems, but uprooted artistic traditions. As Britain usurped power from Indian princes across the northern plains, royal patronage of miniature painting and other arts diminished, casting painters and artisans adrift. The introduction of Victorian-style art academies in the mid-19th century was a process of Westernization that transformed the thinking and practice of Indian artists. British-run art colleges opened in Calcutta, Madras and Bombay to instruct young Indians in European naturalism and history painting. John Lockwood Kipling, father of the Nobel Prize-winning chronicler of British India, was principal for many years of the Sir Jamsetjee Jejeebhoy School of Art in Bombay, where Rudyard Kipling was born.

Traditional Indian art, conceptual and symbolic in nature, had little affinity with the perceptual bias of Western art and the Victorian view of drawing as a mechanical act of portrayal akin to a science. The deliberate disregard of Indian aesthetics in colonial art academies reflected a strategy of cultural imperialism meant to demonstrate the superior technical skill and enlightened morality of Western artists. In response to rising Indian nationalism in the 1920s, however, these art schools began to include imagery from Mughal painting and Hindu sculpture, hoping that by allowing students access to their own traditions they would extinguish the possibility of outright rebellion.

During the war years, a number of talented Bombay painters were mentored in the syntax of Cubism and Expressionism by a few German Jewish art collectors and connoisseurs who had landed in India fleeing Hitler. Despite the racial tensions inherent in the relationship between older European mentors and Indian apprentices, the Germans were an important conduit of firsthand knowledge about modernism. In the symbolic, hybrid art of Picasso, Rouault and other abstract artists, the rebellious Bombay painters discovered a stylistic idiom that came more intuitively to them than the stilted naturalism of the British academy. In 1947, the year of India’s Independence, the most combative of the student rebels from Bombay’s J.J. School of Art, a Goan Catholic named Francis Newton Souza, founded the Progressive Artists Group with five other painters, laying the cornerstone of India’s modern art movement.

Maqbool Fida Husain, Marathi Women, 1950

Of the original Progressives—Souza along with Krishnaji Howlaji Ara, Sadanand Bakre, Hari Ambadas Gade, Sayed Haider Raza and Maqbool Fida Husain—it was the poor, self-taught Muslim cinema billboard painter, Husain, who ascended to become India’s most acclaimed artist. The legendary Husain’s star rose in the 1950s and did not diminish until his death in 2011. Sadly, Husain spent his final years in exile in Qatar, driven out of his homeland by Hindu fundamentalists enraged over his controversial nude paintings of goddesses. Despite the brief existence of the Progressive Artists Group, which disbanded by the mid-1950s, when most of its members left for Europe, hoping to win recognition in the West, almost all important artists working in mid-century India were linked to this circle of visionaries. Husain’s career best traces the trajectory of Indian modernism from its origins in rebellion, to its early patronage by a tiny, cosmopolitan elite, to its recent explosion on the international art market.

The major auction houses now hold annual sales of modern and contemporary Indian art in London and New York, and recently Indian auction houses have established themselves as formidable players, a significant step in decolonizing the art market. A landmark museum of modern and contemporary Indian art is being built in New Delhi by Kiran Nadar, the country’s biggest collector, scheduled to open in 2026. The first work by an Indian modernist to cross the million-dollar mark was “Mahishasura” by Tyeb Mehta, an associate of the Progressives, which sold at Sotheby’s in 2005 for $1.58 million. Surprisingly, it is the work of a rare modern woman artist that continues to break auction records.

In 2023, The Story Teller, an oil on canvas depicting rural women gathered in a courtyard, by Amrita Sher-Gil, a flamboyant half-Indian, half-Hungarian libertine, sometimes hailed the Frida Kahlo of India, became the most expensive work ever sold by an Indian artist at $7.8 million at auction in New Delhi. Sher-Gil, who spent her early years between Europe and India, studied at the Ecole des Beaux Arts in Paris before returning to the Subcontinent, deciding her “artistic destiny” lay in India. She traveled across the country, mainly painting the lives of rural women, and on the eve of her first solo exhibition in Lahore in 1941, died suddenly at the age of twenty-eight. A lone star, Sher-Gill preceded India’s modern movement, and her prolific body of work lay neglected for several decades. India has now embraced her remarkable legacy, deeming her paintings national art treasures that may not be sold outside the country. In my novel, Jaya discovers a small book about Amrita Sher-Gil and is profoundly inspired by her.

I doubt any such book actually existed in the 1950s. For many decades, India’s best artists saw little appreciation or financial reward in a nation left impoverished by British rule and shattered by its violent end in the country’s Partition. Now, a deep-pocketed, proud elite, riding a wave of unprecedented economic success with the tech boom, is investing heavily in the Progressives and their descendants. This late recognition of modern Indian art, the emblem of a confident new national identity, may signal the final end of colonialism’s long hold over the Indian psyche.

Amrita Sher-Gil, Hill Women, 1935